Bentz Boats History

Bentz Boats History

Darell Bentz founded Bentz Boats in 1972 in Lewiston, Idaho to supply other outfitters who wanted boats like he had built for Intermountain Excursions, his outfitting business. The Salmon River and Snake Rivers of Idaho have always presented unique challenges for powered boats. The hundreds of miles of navigable water, wildly fluctuating water flows, and vast stretches of river located far from road access require rugged, reliable, powerful, and responsive boats with larger than normal fuel capacities and low maintenance requirements. Bentz had proven he could build a boat to meet those challenges.

By 1996, Bentz Boats had outgrown their original facility on Bryden Avenue in Lewiston. They purchased two acres at 155 South Port in the new South Port Industrial Park and built a 7200 sq. ft. building to house their manufacturing plant as well as sales and design offices. In 2003 additional facilities were built to construct vessels up to 65′ in length. Launch facilities on the Snake River are close by and provide easy access for the on water tests that each boat must pass.

Bentz Boats has acquired an international clientele not only for their superior boat design but also because they offer on-site operator and maintenance training anywhere in the world. Bentz Boats has built boats and trained operators for customers on the Arun River in Nepal, the Ganges River in India, the Essequibo River in Guyana, South America, and numerous rivers in Alaska and Canada.

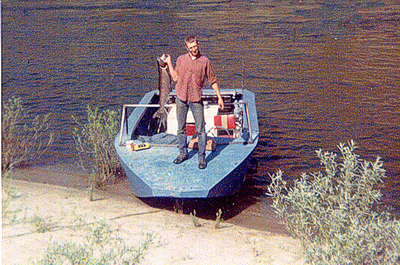

Darell Bentz, Bentz Boats

Darell Bentz, Bentz Boats

Darell Bentz has been working to perfect the whitewater jet boat hull for four decades, even though when he started, he was told these aluminum boats would soon be replaced by fiberglass and disappear. Today, his aluminum boats sell for tens and even hundreds of thousands of dollars, and are in demand all over the world.

On how he got involved with river running:

Actually I was raised on the ranch of White Bird. We weren’t around rivers – well, the Salmon River was there but we weren’t around boats when I was a kid. My brother and I rafted the upper main Salmon in 1964, 65 from Panther Creek to below Vinegar Creek on 4th of July weekend we rafted that. We did some rafting on the lower Salmon, rafted the lower Salmon. Got hung up on the rivers. Fell in love with the rivers completely.

When I was 18 years old I worked for the forest service and was on a trail crew and actually it was a bad fire year. I spent most of the year fighting fires. We actually got bussed to Mackey Bar and were on a fire up the river from Mackey Bar. At that time Al Tice owned Mackey Bar. He had two boys and he had some very early, early vintage jet boats – fiberglass – up there. I got jet boated up to a fire in 1961 at Gains Bar above Mackey Bar on the upper main Salmon.

I was just totally fascinated by the whole thing. We jet boated to the fire and then when the fire was over I was helicoptered out. And then I didn’t know whether I wanted to be involved with jet boats or become a helicopter pilot.

On how he found his first jet-boat motor:

We floated the north fork of the Clearwater River one summer when I was going to college – it would have been about 1966, summer of 1966. That spring, Potlatch Corporation had lost a jet boat in the North Fork. They used to do a log drive. There weren’t many jet boats at that time but they had a jet boat built – a plywood one – and used it only 2 or 3 days in the log drive that spring and had an accident with it and I think one man drowned and they lost the boat. The river was high in the spring of the year, spring run-off. It was in their annual log drive, which was quite an event.

We floated the river in August. The river was low and clear and just by fluke accident we found the engine and the jet unit out of that boat. Through a little bit of a trial and error we ended up recovering it. We didn’t even know what it was when we got it, but it didn’t take too long and we figured it out. We decided we need to build a jet boat. So that’s where the plywood jet boat came from.

We operated that jet boat some and got I guess more hung up or more infatuated or more obsessed with the rivers. When I graduated from college in ’68 I graduated with a degree in animal science and I had some job offers back in the Midwest and different places. I finally decided I wanted to move to Lewiston and I got a job with the Lewiston Grain Growers as a feed specialist and I moved to Lewiston – my wife and I moved to Lewiston not because of the job opportunity in Lewiston but because the rivers were here.

On getting into aluminum boat hull design:

I helped another fellow build some aluminum jet boat hulls for Valley Boat, and we changed the bottom design on every one of them and ran them a little bit and I had an opportunity to learn a little bit about jet boat hulls, but still had very little experience. I did that for a couple of years and then built my own first welded aluminum jet boat in 1970. I put a lot of thought into the hull design, into the bottom design and into the bow design. It didn’t come out quite the way I wanted it to but that boat is still operating and it’s owned by a relative of mine outside of New Meadows.

It kind of evolved from there and I got the whitewater bow design where I wanted it and where it seemed to work well. I built boats for Gary Amacost from Hells Canyon Adventure, who started a jet boat business in upper Hells Canyon from Hells Canyon dam downriver through the big waters, through the big class 4, class 5 waters in upper Hells Canyon. I ended up building several boats for Gary and his son Brett.

They could operate the boat for a year and then I could look at the boat at the end of the year and see where structural problems were and do whatever it took to make it work better. Zeke West was another early one on the upper-main Salmon. Zeke operated out of the White Water Ranch.

On how he developed his designs:

No engineering background. I think some of it was just plain luck, but I always wanted to build a really tough boat. I built a boat for my dad in 1972 when he was alive. He wasn’t a very good driver and I thought he might wreck the boat and sink it and I was worried about it so I decided I would just try to build the boat so tough that he couldn’t destroy it and he didn’t destroy it. That boat, today it has impacted in excess of a hundred rocks. There probably isn’t a boat in Idaho that has gone the places that boat has gone. I think it’s on a 7th engine at this time. It’s still got the original bottom in it. It has been rearranged a few times.

That was an early boat and we learned from all of those boats. I learned from every one of those boats how to make a boat structurally hold together better. Upper Hells Canyon has got big rapids, big hydraulics. When you are hauling passengers you need to be able to do that safely. The boat has got to do 2 things. It’s got to perform. It’s got to have enough power. It’s got to perform in that way but it’s also got to be able to maneuver in heavy hydraulics and in technical wakky water. And so I’ve basically spent a lifetime trying to figure out how to do that.

Those boats have got to be able to turn and handle in rocky technical water and they’ve got to be able to go where you want them to go day after day. I’ve learned a lot really from the guys who make their living day after day driving those boats.

An obsession, yeah, yeah. I came up with a bow design and a bracing design that is totally unorthodox – but it works. It works and works very, very well in that a bottom bracing design has evolved. It just continually evolved over the years and is still evolving.

The Coast Guard-inspected boats are looked at every year in an annual inspection, and then every 5 years they pull the floors and look at the bracing and inside of those boats. They’ve told me that our boats hold up better long term than any other boat from any other manufacturer that they look at.

We’ve got a boat here in the valley that belongs to an outfitter that has got approximately 18,000 hours on it between Lewiston and Hells Canyon dam. That represents an awful lot of hours. The boat was built in about 1989 and it has structural defects that we’ve overcome since then. So our boats now I think are stronger than they’ve ever been.

On how the business has changed:

I used to do all the drawings. I took some mechanical drawing courses in both high school and college so I’d do those drawings. And if I’d make a mistake would have to erase it and go back and redo it then submit it to the Coast Guard. Now we’ve got an AutoCAD program and a young engineer who runs it and you can change things on boat designs, you can sit there and just change things very, very easily and that technology I think is absolutely great. It allows us to do a better job, a more precise job.

We can work up the parts on the AutoCAD and then if we want to build mass produced parts we can do that. Some parts in boats you can build numbers of. And that technology has certainly progressed and we’ve been able to take advantage of that.

Emails?

We didn’t know what an email was. Didn’t even know what a fax was. And it wasn’t easy. And the communicating by phone – my hearing was a lot better than it is now. But communicating by phone those distances it wasn’t easy but we managed. Got it done.

Engines in jet units have improved tremendously and particularly in diesel. New diesel engines with high performance, lightweight high performance turbo diesel engines. They’re getting lighter and better all the time.

Is there a perfect bottom design for all conditions?

No. You’ve got to recognize water conditions and where the boat is going to operate. These boats in Idaho, they operate on the Salmon River and upper Hells Canyon. You’re in rocky, technical waters on the Salmon River. Some really shallow places in low water conditions. Not so much the big hydraulics that the Snake River has got. The Snake River is a deeper river, big hydraulics, but when the river gets low certain times of the year those boats have got to maneuver pretty precisely.

A bottom design for the Snake River is just a little bit different than you do for the Salmon River – if that’s where the boat is going to stay. I’ve experimented with delta pads, tapered deadrise bottoms, all different styles of different tapered deadrise bottoms, constant deadrise bottoms and have come up with my own theories on it.

We’ve got boats operating in Alaska that have to run over gravel bars, carry loads over gravel bars where the water is very, very shallow and they have to be able to do that successfully day after day after day. And then we’ve got boats in Alaska that go up the Stikine River. Silt laden, braided. And then on the very upper end of the Stikine you’ve got some big rapids.

And then we’ve got boats that operate in salt water – whale watching boats. So you’ve got all different kinds of water conditions and it takes different bottom and bow designs for those different water conditions.

You take a rapid in Hells Canyon. That water is moving over big rocks, uneven surfaces, and that water can be going 30 miles an hour and it is creating those hydraulics and those waves. Those rocks aren’t moving but the water is. In the ocean, the water is not moving. It might be moving maybe 5 miles an hour, but basically that water is not moving but there are waves, the waves are moving. In a river the waves stay in one place but the water is moving. In the ocean the waves are moving but the water isn’t. So you’ve got 2 totally different water conditions and of course in the ocean you don’t have a shallow water depth problem.

So it takes different bottom designs. The deeper the V that you put in a boat, the softer it rides but also the more unstable it is. The boat will be more tippy. We struggle with that in Alaska with our whale watching boats because they’ve got to be stable in all different kinds of weather conditions.

What has helped the most?

Probably the biggest thing is our customers. And loyal customers. I’ve learned more about building boats from probably people who don’t know the first thing about building boats – but they know what makes a boat run good. They make their living with those boats. They run them day after day after day after day and they watch other boats on the water and they know what works and what doesn’t. And some of those guys have become and have been really good friends over the years. They’re some of my harshest critics. And I think that’s great because it only makes you do a better job.

On his true love, exploring rivers:

Both my brother and I do have pretty adventurous spirits. That’s a passion for me. I took a jet boat from Lewiston to the mouth of the middle fork of the Salmon in 1972 and for me it was a big thrill. I ran a jet boat on the upper Salmon, took a jet boat to Corn Creek because of the challenge every year for over 20 years and still do it on occasion. The same thing with upper Hells Canyon. I took a jet boat to Hells Canyon dam in November of 1974. To me at that time it was a big challenge and a big thrill and it gives you I guess a little bit of an adrenalin rush that’s hard to get over.

Exploring rivers, trying to explore rivers, I’ve been very, very fortunate to be able to do that. Been able to do the Ganges River in India and gone to South America and explored a number o f different rivers and a little bit in Alaska.

On going where no one else has:

In 1995 I had a 28-foot twin engine jet boat that I really liked. A guy came down from Wrangell, Alaska, and looked at that 28-foot twin and he said, ‘Where I run on the Stikine River, there’s no way you’d get a big boat like that up there.’ And I said you’d be surprised what these boats will do. The young guy who worked for me on the lower Salmon and in Hells Canyon took my boat and took the guy for a ride on the Clearwater.

The river was really low, it was running about 3,000 CFS or just slightly lower. But he took the guy up the Clearwater and it blew him away. He couldn’t believe how the boat maneuvered and handled and turned and how shallow it would run. And he came back and he said I want to buy that boat and I said I’m not really ready to sell that boat. He said well, I want to buy it. I want to buy that boat. I was outfitting and I said I need that boat for a while here. He said okay but I’m going to buy it. And I didn’t agree to sell it to him until he said, if you’ll sell me that boat and come up to Wrangell, we’ll take that boat up the Stikine River to Telegraph Creek, which is 165 miles up the Stikine River. He said we’re going to get hung up on a sand bar someplace up there before we get back, but he said if you’ll sell that boat to me we’ll do a trip up there. So I sold the boat to him and we went and did the trip.

At that time, nobody had ever run a boat past a big rapid above Telegraph Creek. There was an old Indian chief there and when we showed up with the boat it was kind of an event. We were the first boat that had gone there that year. So this chief came down and said big rapid, you don’t want to go up there. And I said well, I’d like to go up and look at it, just see if it’s run-able. Go look at it. I asked the chief if he would like to ride with us. No, I’m going to get on the road up above and watch. And the guy who owned the boat said from here on this boat is yours. We got up to the rapid and it was about like Rush Creek in Hells Canyon. And so we ran it 2 or 3 times. And there was a road that went around above and I think the whole village was up there watching us.

We went on up the river and actually we ran some rapids that were worse on up the river and we didn’t turn around because couldn’t go any further, we turned around because we were low on fuel at that point.

There was a place down the river where the Indians were fishing. And we pulled in and that chief was there. And I asked him if he wanted ride back down the river with us. So he rode back down the river with us.

And since then, now we have built boats that operate and run that water all the time.

On wide-ranging deliveries:

You never know when opportunities are going to come up. Like in 2011, this opportunity to deliver a boat to an Eskimo village of Kugluktuk north of the Arctic Circle at the mouth of the Coppermine River, 2,021 miles from where we put the boat in the water.

We were the only boat on the ocean in, oh I don’t know, 800 or 900 miles of ocean. I would have to rescind that just a little bit because there is one Eskimo village from the mouth of the Mackenzie, and there are small fishing boats around those villages. That’s a pretty isolated place.

We shipped that boat up there and within the same month we shipped a boat to South America to Guyana. So we had one boat that went to the equator and one boat that went to the Arctic Circle within a month of each other.

On growing the business:

It wasn’t very successful for quite a few years. I just had a strong passion to do it and build better boats. We started my first aluminum jet boat in 1970 and then we built a boat or 2 a year for somebody. I’d build a boat for somebody that I knew or a friend. So we were building 2 or 3 boats a year and it evolved very slowly.

When I first started, the owner of Valley Boat and Motor at that time in 1968 or ’69 was a boat businessman. I was just out of college, had no boat experience. But he said you know these aluminum jet boats, there are going to be a few of them built, but there will never be very many. He said the future of jet boats in this valley is fiberglass. He said I would never get very serious about aluminum jet boats. He knew a lot more than I did and I believed him at the time. Since then the jet boat manufacturing business has done nothing but evolve and grow in this valley. And it’s a hot bed of jet boat manufacturing. There are some good manufacturers here and a lot of nice boats are built here in the valley.

Has this ‘cluster’ of boat-builders helped your business?

Yes it has. Getting a skilled worker pool has been a problem. It’s getting better because there are enough manufacturers here and enough people that it’s not the problem that it once was.

I think the competition has made everybody in the manufacturing business better. I think it’s probably a little bit harder to get started now than it was when I started although I don’t know that. There are a lot more boats built now, but a lot more people doing it. Young guys work for you and they learn how to build boats and they want to go on their own and that’s a continual deal that happens all the time. And it will always be that way.

I was no exception when I started. When I started I learned. I wasn’t that good of a boat builder but I learned pretty fast and I was a better boat builder than I was a business person and it took a while to learn the business part of it for me. I had the passion for the boats and the design and trying to make those boats work and work in different water conditions and I was never ever happy with a boat design. Never. And there are other people building boats and the competition has been good for everybody.

On his first broken back:

I broke my back in a racing boat the first time – the first time I broke my back. The second time I broke my back was in India on the Ganges River in a rapid called the Wall.

I’ve got a good friend who’s retired now but he was an orthopedic surgeon. When I broke my back the first time I ended up at his office and he was looking at the CAT scan. I was laying there on the table and he told me you’re not going to be doing anything for 60 days. You’ve got a compression fracture and this vertebrae crack to so many degrees, broken in so many degrees and this and that. He said you’re not going to be doing anything for about 60 days.

And I was laying there on that table and I was thinking, you know, the Clearwater jet boat race comes up in about 63 or 64 days and I asked him, you know that Clearwater jet boat race comes up in about 63 or 64 days. What do you think the possibilities are that I might be able to race in the Clearwater race? And he looked at me for about a minute and never said a word. He just looked at me and pretty soon he said you and I, we’ve elk hunted together and we were talking about going elk hunting when we’re 70 years old. He said, do you remember that conversation? I said yeah I do. He said there is a possibility that you might be able to elk hunt when you’re 70 years old but I’m going to tell you something. You get in that race boat and you damage that vertebra one more time, you’re going to spend the rest of your life in a wheel chair.

That ended my racing career right there.

The epic story of the second broken back:

Two years later in 1993 I sold this boat to India, and the family that bought the boat wanted me to go over there and give the driver some operational training and also see how far we could go up the Ganges River in the Himalayas. I was pretty enthused about that. Then my doctor friend told me whatever you do when you go over there, don’t do anything to get yourself hurt. And I said why is that? He said 2 reasons – #1: India’s hospitals are not clean and #2: India’s got one of the highest incidences of AIDS of any place in the world – at that time. He said so don’t do anything to get yourself hurt while you’re over there.

I ended up breaking my back the second time in that river. It was an all-night drive. I broke my back about 3 in the afternoon or 3:30, something like that. And we were up in a place that was technical, the water was technical. It was like the lower Salmon in low water and I couldn’t drive. I couldn’t drive the boat. We had to get the boat down the river about 3 miles to where we could get access to a road. The guy that I had been training had to drive the boat and he was nowhere near ready or prepared.

I couldn’t give him any help at all. I was laying down on a bench seat on the side. I knew my back was broken. I didn’t know how bad but I knew it was broken because it felt just like it did when I broke it before. So he had to drive the boat and another guy tried to help him. They smacked 3 or 4 rocks getting down there, pretty hard but we made it. We didn’t knock a hole in the boat.

They had to carry me – it was just like upper Hells Canyon right up through some rims and some rocks and stuff to get up to where there was a road. There was a chaise lounge chair in the boat that they had taken and they could make it out straight, and those guys carried me up there and the first car that came along was a little French car called a Le Car. They’re about this wide. I rode in the back of that thing until sometime after dark, laying on my side with my knees up under my chin. We got down to where we had started from and then got transferred to a Toyota LandCruiser and travelled all night over bad roads to get to Delhi to a hospital. Got to the hospital in Delhi at 5 the next morning.

The first thing that happened was they put me on a gurney and went in and a nurse came up to me. She was wanting to do a blood draw and she couldn’t speak a word of English and I just looked at her and shook my head and went like that. And I was not really in very good shape. I was really hurting, been riding over bad roads all night. She went back and she came out and she showed me she had a sealed sterilized container that a needle was in and she took the needle out of that and so I let her do the blood draw.

The doctor came in the next morning about 8 and I told him that I had a broken back, I was sure I had a broken back. The hospital didn’t have any x-ray equipment or anything like that and he said we’re going to have to do an x-ray. We’re going to have to schedule an ambulance for you to go over to another hospital that’s got an x-ray machine.

At that time Delhi, India, had I think 30 ambulances for about 8 million people and it took a day and a half to get the ambulance there, so it was the following afternoon and the ambulance showed up and these 2 guys came into my room. They just walked into my room and got one of my arms around each one of their shoulders and dragged me out the door.

It looked like an old Wholesome bread from the ’50s and ’60s. I didn’t see an oxygen bottle in there but it had kind of a bed deal on one side of it and so they dragged me up there and put me on that and drove about 45 minutes or an hour to this hospital and got the x-ray done and brought me back. The doctor looked at the x-ray the next morning, it was such poor quality he couldn’t tell anything from it. So he said we’re going to have to do an MRI and I said do they have an MRI in Delhi? He said we do but we’re going to have to schedule another ambulance. Went through the same procedure, another day and a half, a different ambulance, different ambulance drivers. But went through exactly the same thing. They just dragged me out and loaded me in the ambulance.

Got the MRI back, the doctor looked at the MRI and he didn’t believe I had a broken back before then but he said you do have a broken back. He said we don’t dare move you for 60 days

I said doc, I really want to go home. I really would like to go home. He said I don’t see how it could be done. He thought about it for a while and he said we might be able to put you on a gurney with a special nurse to go with you, but he said it’s going to take up about 5 seats in an airplane and it’s going to be expensive to do that and we’re going to have to send a special nurse home with you.

But what he did – he had a guy come in and took a plaster of paris of my back, my whole back, and they made a fiberglass body cast for me with big wide Velcro straps in the front and it really stabilized my back a lot. He said with that you might be able to go home. I said I’d really like to do that if possible. If there’s a possibility I would like to be able to get a second opinion from an orthopedic surgeon and he said I can arrange that. I said figure out the travel arrangements, and he said I’ll get a travel agent and I’ll get the orthopedic surgeon and we’ll have a meeting right here in your room and we’ll see what we can work out. That’s what we did and ultimately I got home. And Lewiston, Idaho never looked so good when I got home.

The aftermath:

My brother had to go over there after that. The boat was up the river and there was no way they could get it down the river. He went over to finish the driver training and get them so they could operate the boat more efficiently and a little bit better.

But it healed up. I can walk, I can do most things and I’ve been able to drive a jet boat and I’m a very, very fortunate guy. I had a bilateral lung transplant in 2007. I was trying to get the doctor to release me to drive after the transplant and he wouldn’t do it for about 4 months and when he finally released me to drive a vehicle I said I can drive a jet boat can’t I? He said I don’t know about that and I said a jet boat is not harder to drive than a car is. I should be able to drive a jet boat and he said okay, you can drive a jet boat.

Any rapid too big?

I’d be lying if I said no. You’ve got to make a decision someplace. You’ve got to make a decision whether you’re going to try that rapid or you’re not going to try that rapid. And you study it and you study it and you decide whether you think you can make it or not and you’d better be right in that decision.

We turned around on a rapid on the upper Essequibo River in Guyana that I was pretty sure that I could get through, but we had 2 boats and we had about 20 people total with all the camp gear and stuff. We were 500 and some miles from nowhere through rain forest – jungle – and if you’ve tried to walk through that jungle it’s difficult. It’s difficult to walk a mile and we were just in an extremely remote place and we turned around. But I really wanted to try it.

What’s the best part?

There are so many aspects there. Not just running the whitewater and the rapids. To me that’s a big thrill. I really, really enjoy it but the scenery, the spectacular scenery and I’m an avid fisherman. I love to fish. Being able to get where there aren’t a lot of other people to fish. And exploring, just exploring and seeing places you’ve never seen before. Being able to explore places. That upper main Salmon – I’ve been up there a lot and it’s still just a wonderful place to see. And people that have never been up there, it’s just a great experience. Seeing game and hunt. We still go on the upper Salmon every fall and jet boat to camp up above the end of the road above Riggins and trail stock in and elk hunt every fall. Probably enjoy it as much as we did on the first time we ever did it.

The first time I ever went up there elk hunting was in I think 1974 and still enjoy every trip.

On staying in Idaho:

If I’d taken the job in the Midwest my life would have been totally different and I’m so happy that I didn’t do that. I haven’t travelled every place in the world, but I’ve been to Europe and I’ve been to South America and I’ve been to Alaska, up in the Arctic, been to India, Guyana, a lot of different places in the world. I think Idaho is the best place there is. Just to be able to live in the northwest. Anyone who lives in the northwest is just an extremely fortunate person and if you’re fortunate enough to live in Idaho in the northwest you’re even more fortunate.

We’ve got not just rivers, whitewater rivers. We’ve got just some absolutely great whitewater rivers but the hunting and the fishing and the scenery. It’s a great place to live. It’s certainly not as easy a place to live as some others. I was working really hard in the late 70s in the pool construction business and just working a lot of hours – 80, 90 hour weeks – and had a friend that came by one day and said man, I’m going bass fishing. Why don’t you come and go bass fishing with me? I said I’d really like to do that but I’ve just got so much work to do I don’t dare do it right now. He said you know what? If you’re not going to take the time to go bass fishing and enjoy what we’ve got here why don’t you just move to California where you can make some real money and don’t worry about it? I thought about that – he was right.

We might not make as much money here. The average person here may not make as much money as you could make in Los Angeles or different places in the world but we sure have a great lifestyle. I’ve been very fortunate to be able to participate in some of that and explore the rivers we’ve explored.